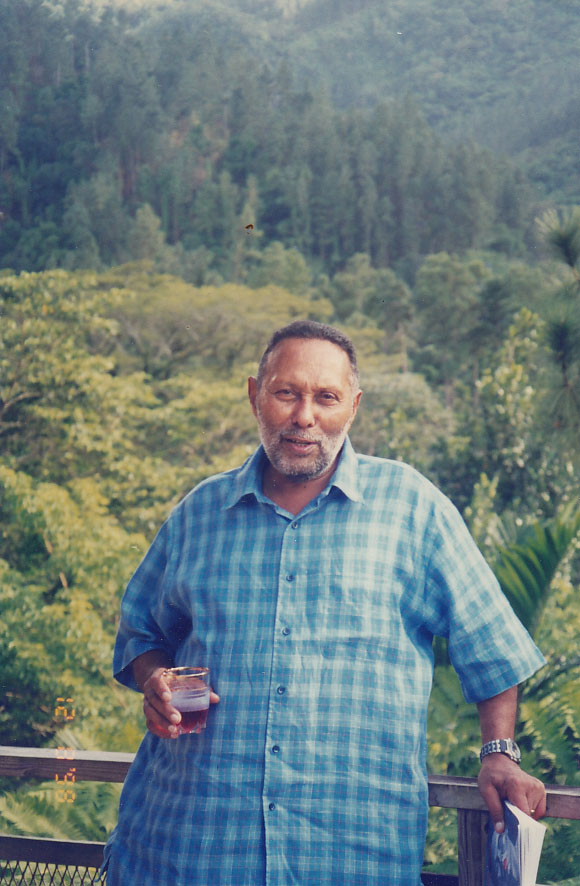

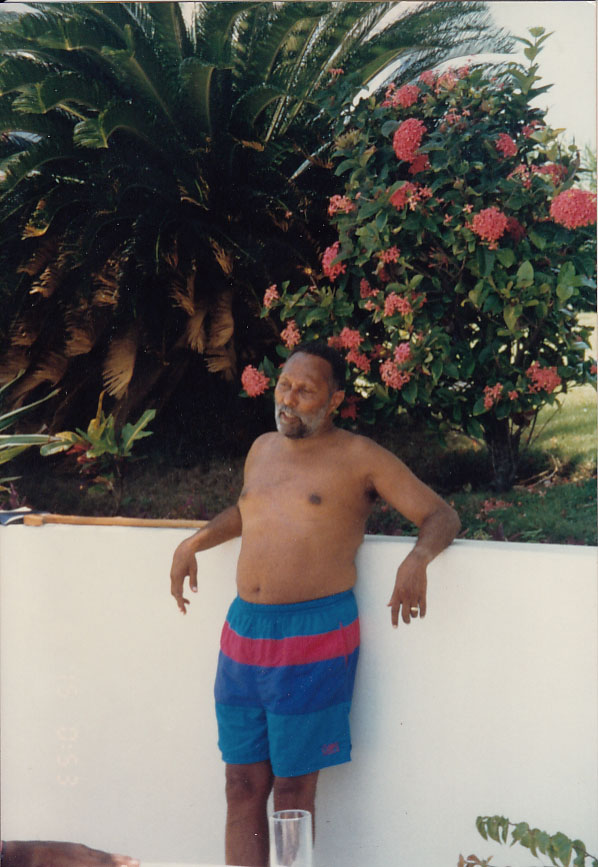

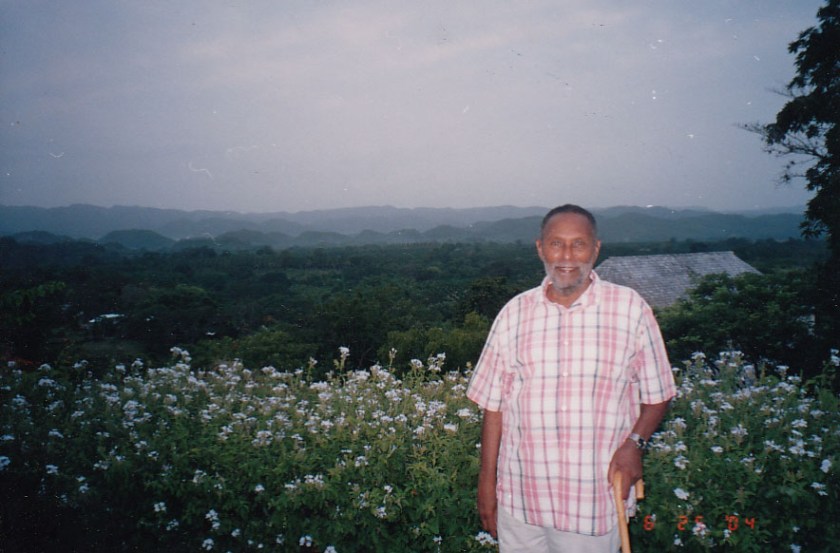

It’s about six months since the world-renowned intellectual Stuart Hall passed away in London after years of ill health. In Jamaica where he was born and brought up Hall remains largely unknown so that it took local media a few days to register the fact of his passing. It was scandalous then and remains scandalous today that the highly acclaimed film about his life and work, The Stuart Hall Project, has yet to be shown in Jamaica. A friend who attended the recent Global Art Forum at Art Dubai 2014 remarked that she had seen busloads of people going to view the film which was a highlight of the programming there. I excerpt below a question Ibraaz Editor-in-Chief Anthony Downey asked the director of the film, John Akomfrah, at the forum. It will give a sense of how the film and its subject, so little valued in Jamaica, are viewed by the rest of the world:

AD: …You mentioned Stuart Hall and the pivotal, seminal importance of Stuart Hall for your generation. Certainly for my generation, coming to England in the late 80s, Stuart Hall’s work opened my eyes to the potentiality not only of theory but of thinking, clear thinking; how you could assess a situation in a manner in which it had never been considered before.

I’m thinking now as well of your most recent film The Unfinished Conversation (2012), also known as The Stuart Hall Project. I’m wondering – this must have been a labour of love, this could not have been an easy film for anyone to make, because, in effect, one is dealing with the father figure; one is dealing with the person who made a lot of what we do today possible. He is, effectively, the father of multicultural studies, but equally he transcends that.

Could you talk a little bit about how that film came into being, and what you see it as? Because it’s taking on a life of its own now; it’s transcending you. It’s being shown worldwide, it has garnered awards, and it will be shown tomorrow here in Sharjah. Can you talk a little bit about how it came into being and the importance of that, and where you see it going, or indeed, if you can?

For the full interview go here.

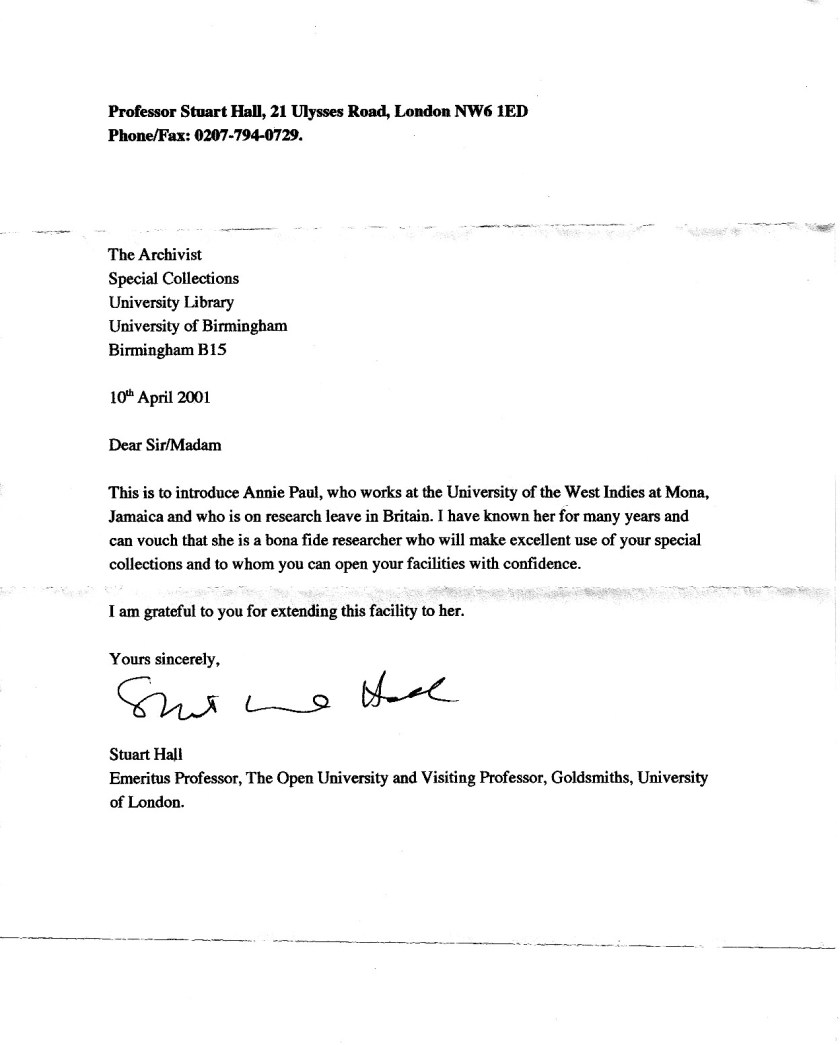

Perhaps the most moving elegy to Hall was written by Columbia University-based David Scott, also Jamaican, editor and founder of the journal Small Axe, who is working, among other things, on a biography of the acclaimed cultural theorist. I excerpt below from his posthumous letter to Stuart and ask that we reflect on how and why a country that takes such pride in its triumphal culture is incapable of celebrating a son–widely acknowledged as having put culture on the curricula globally as an object of study–who was as much a trailblazer as Usain Bolt.

So here then is Scott’s letter:

Dear Stuart,

There remains, as you may well imagine, a lot to say. That is why I have, once more, taken refuge in writing you a letter, selfishly perhaps, foolishly, yes, but it is for the sake of my own belated clarification, and to sustain the dialogue (henceforth, alas, a fictive one) we have been engaged in these past many years—and all without heed, I apologize in advance, of your undoubted desire to be done with the bother and burden of all this.

But there are now so many conversations left stranded in the middle, Stuart, by your lamented departure, cut off without ending, without prospect of an ending. Death does that, though, doesn’t it, in an uncanny, unforgiving sort of way. Death is the sharp knife-edge of our finitude, the moment (however it comes, timely or untimely) when we are overtaken by the irreversible—and the ineluctable—fact of our mortal being. It is the last conjuncture, isn’t it? As you once said to me, somewhat gravely, ruefully, apropos of what I can’t now remember: Life unfolds in one direction only. It does. I take that to be an existential truth, with tragic implications. Whatever the Augustinian distensions of temporality we are inclined to imagine, whatever our hermeneutic desire to refute or refuse the linearity of time’s arrow, we all round the corner on this particular crossroads—Papa Legba’s—where we find ourselves summoned to render up what is owed for what we have spent. The one thing we are guaranteed: death is simply the price we pay for time. As we made our way behind you through Highgate Cemetery that bright and private Friday morning this past February, with strains of Marley’s great elegy, “Redemption Song,” still plaintively resonant, we all, I think, noticed Marx pause his ruminations and nod his fraternal welcome, and, just next to him, our own Claudia Jones whispered a dread chant of greeting; and as I watched you being lowered caringly into the ground’s reluctant embrace, I almost cried out with Derek Walcott, “O earth, the number of friends you keep / exceeds those left to be loved.”1

But it is finitude, Stuart, about which I want to talk to you on this occasion, the strange, haunting sense of a last conjuncture. Because this is something we talked about a good deal in the last years—sometimes directly, mostly obliquely—as talk about your life and your work (an admitted obsession on my part) came to be shadowed by talk about the immediacy of pain, the permanence of discomfort, the long, difficult nights without sleep, the creeping anxieties, the dispiriting experience of a body less and less under your command. We spoke, too, occasionally, about death—not only its frank imminence but also its peculiar immanence, how it comes from within as much as from without. And yet, even so, Stuart, finitude is not exactly a word many would readily associate with your name. Too lugubriously Heideggerian in feel, maybe; too complicit in a fatalistic sense of limits, constraints; too redolent of a realm of necessity. So much of your life was committed to the construction of new possibilities out of seeming dead ends, new times and new identities out of old, beleaguered, frozen ones, that there is undoubtedly something perversely paradoxical in this image of you face to face with your finitude, not a philosophic abstraction now, but face to face with what you might have called, with a slow, sardonic smile, the final play of contingency. So, I wonder whether finitude isn’t precisely a word that bears reflection in relation to you because of what it illuminates about the tension between what you are given and what you can make.

I want to talk specifically about finitude and writing, more specifically, about my impression that the growing awareness of the coming end increasingly shaped the exercise of writing, especially the uncertain, or anyway not-so-straightforward, exercise of composing your memoirs—the last, definitive, story of yourself. What do I mean? I know you would have asked me that, Stuart, leaning slightly forward in your chair and regarding me with a resigned but skeptical air, trying to discern whether on this occasion our conceptual languages were overlapping, or at odds. I don’t mean anything very mysterious, of course. You already know that it has always seemed to me that for you writing was a way of moving on, of not standing still; it was a way of not being the same, of occasionally changing yourself, of saying the next thing rather than the last thing. Indeed, there was never for you a plausible “last” thing to say. This was deeply a matter of the politics as well as the poetics of writing. For you, therefore, writing was always to have an orientation toward futurity. I don’t think that the past as such ever much enchanted you; you certainly never reified it. The challenge of writing, then, was to subject the present to a form of redescription—what you famously called “reading the conjuncture”—that aimed to loosen its bondage to the past, to release it from its congealed assumptions so as to make possible a contingent practice of reinvention.

This is why, as I keep repeating, the essay-form so appealed to you as a genre of writing. The thing about the essay-form, it seems to me, is its embodiment of a mobile temporality so conducive to your temperament and the general ethos of your style. The essay is always, precisely, moving on. It has, in this sense, an active more so than a contemplative character; or rather, however meditative it may be, it always suffers an internal restlessness, an agitation of spirit that drives it in one direction or another—or in one direction after another. This is what enables the essay to evade closure and to defer its rendezvous with finitude. The essay is a thinking form—thinking that is inherently situational, occasional, embodied. One might say that the essay-form is a mode of presencing, of being present, of voicing presence, within writing. In this sense it is as close as nonfictive writing can get to the uneven grain of an audibly speaking voice.

Scott’s poetic tone and the probing register of his elegiacal missive are not ones we often come across in intellectual work here where public debate and discussion seem frozen at certain basic levels. Building Brand Jamaica. Attaining sustainable growth. Poverty alleviation. Reducing risk perceptions. The buzzwords trip off our tongue and down the drain. Gleaner columnist and Nationwide broadcaster George Davis rightly questions the quality of education available to Jamaican youth lamenting the fact that “An essay in university is like honour in the Jamaican Parliament; it’s almost disappeared.”

For the rest of Scott’s letter go here.