On December 5, the day Nelson Mandela finally died, after a heavily mediated, prolonged deathwatch, I was in Amsterdam with Kumi Naidoo, a close South African friend of many years standing. In between hundreds of requests for his comments from global media I managed to sneak in an interview myself. I had originally planned to interview Kumi about his role as Executive Director of Greenpeace International, about the predicament of the Arctic 30 who were still in captivity in Russia then and other environmental issues. After Mandela’s death I decided to include Kumi’s views on this historic passing in the interview, as an ANC activist of many years standing, as someone who knew and worked with Mandela personally, who better than Kumi Naidoo from whom to get a perspective on Nelson Mandela and political leadership in general. This constitutes Part 1 of the interview. In the second part which i’ll post in a couple of days i ask him about Greenpeace, environmentalism and the Arctic 30 among other things. First an excerpt from Kumi’s Greenpeace blog:

I was 15 years old when I first heard the name Mandela, or Madiba, as he is fondly known in Africa. In apartheid South Africa he was public enemy number one. Shrouded in secrecy, myth and rumour, the media called him ‘The Black Pimpernel’. He was able to avoid the police, using several disguises – a favorite of which was that of a chauffeur – until the CIA colluded with the apartheid regime to ensure his capture. In Durban, where I was born and grew up, and all over Africa, he was a hero! Now he is a hero to the world.

AP: Kumi, you knew Nelson Mandela personally, you’ve had experiences with him, you are from South Africa, and I heard you in the BBC interview a moment ago saying something about how you thought the world could best do justice to him, or the best tribute they could pay to him. Could you develop that point for me?

KN: Mandela was very keen not to be understood as an exceptional person. I’ll give you a story. In 2004, I was in Mobutu, Mozambique, to help moderate a discussion with young people and with some senior African leaders which included Graça Machel and Joaquim Chissano, who was President of Mozambique at that time, and these were kids from eastern and southern African countries who had developed a vision of what they wanted Africa to be in 2050, and were presenting the vision. So, when I was moderating the discussion, one of the young people asked the question: “What is your definition of leadership?” And Mandela’s mind flipped back to the forties and he answered it as he would have answered it at that point: “We in the ANC youth league believe in the idea of collective leadership.” So essentially his notion of leadership was a very servant leadership, that you are there to serve not to take. And the reality is today most of our political leaders want to be treated as gods and semi-gods, from the security details to the fuss around them and so on.

AP: They’re more interested in the aura of leadership?

KN: And I think even though he was feted and praised as he was, he always was at pains to say, I’m a human being. And whenever anybody called him a saint, he would say: “If by saint you mean a sinner who is trying to be better, then I’m a saint.” His own sense of himself was a very humble reading, [different] from how the world read him. And, quite often, you had the sense that he was not comfortable with all the accolades that would be, you know…

AP: Hurled at him.

KN: Yeah, in fact, there’s a beautiful one on women. Nelson Mandela once said “I can’t help it if the ladies take note of me; I’m not going to protest.” He also spoke about how, as a human being, he’s made mistakes. In 1995 when I was heading the Adult Literacy Campaign in South Africa I took kids and adult learners to the Parliament to meet Madiba on International Literacy Day. They were excited to have their picture taken with him – the image was to become a poster for our campaign to promote adult basic education – but everyone was anxious; they were asking me what they should say and how they should approach meeting the President! The main line that people had prepared, the kids, and even the adults that were there, was something like, “Thank you, Mr. President,” or, “Thank you, Madiba, for taking time. We know how busy you are.” But when Madiba emerged from his Cabinet meeting he turned the tables. He walked in and thanked everyone for taking the time to see him. “I know how busy you all are and I thank you for taking time to meet me,” he said. In that moment he closed the gap. He was just a human being, a person like them, and everyone relaxed. Within a minute, that sort of thing about the leader and the lead, the gap was closed, and that’s a rare thing.

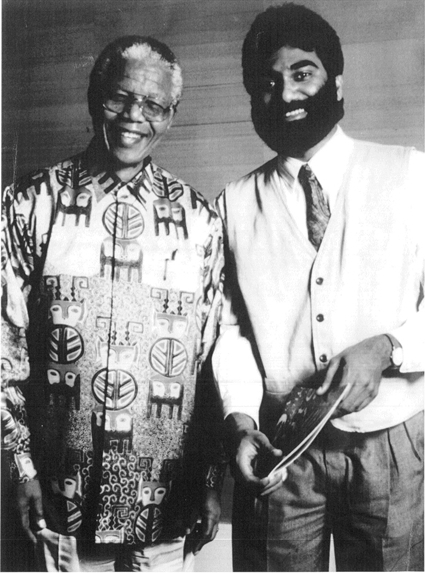

One of the things that I noticed with my own eyes was his ability to engage with kings and queens and heads of state on the one hand, and his ability to engage with ordinary people, equally comfortably. For example, I first met him when I was in my late 20s, in 1993. I was helping facilitate an African National Congress (ANC) workshop to plan its media strategy. I went down to meet him for the first time and you know me I got stupid… I just choked. I said, “Hello Madiba, it’s a real honour to meet you,” and I couldn’t get another word out. Just that one sentence. So during the workshop, he quietly, didn’t make a big fuss of it, quietly asked, “Can I go and say thank you to the people who prepared the food, and the workers of the hotel?” And I followed and I watched what he did and he basically shook everybody’s hands in the kitchen and said thank you to everybody.

I’ve come across a lot of people in my life who talk about poverty and talk about the poor, but you rarely have a sense that it matters to them to the point at which they will be willing to sacrifice something. Yes, they feel a sense of solidarity, but when you speak about the poor, that you actually celebrate the eloquence of the poor, the tenacity of the poor, the perseverance, courage… I mean, to survive poverty is… You know, many people theorize poverty, but so many elements of poverty, individually, for most people who theorize about poverty would be really difficult to even comprehend the individual things. Just take homelessness. If you are homeless, what does it mean not to have a post box where people can contact you; what does it mean not knowing where you’re going to sleep at the end of the day; what does it mean not having a place where you can store what little you might possess. So dealing with homelessness in itself is a huge thing for most people who are commentators [on] or benefactors to poverty. Then you take an issue like living with HIV/AIDS… I mean, you know, where health care is difficult… where people have to struggle for access to antiretrovirals and some still don’t have access to them and all of that, and just confronting that alone, for most people, would be a major challenge. And then you got things like educational deprivation as a result of a conscious apartheid strategy, where the founder of apartheid, Verwoerd, once said, and I quote, “Blacks should never be shown the greener pastures of education, they should know that their station in life is to be hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

AP: Who said that?

KN: Verwoerd. V-E-R-W-O-E-R-D. He was the architect of apartheid. Those legacies still live on. And Mandela’s very strong commitment to education more than anything else, and very strong commitment to children more than anything else, comes very much from a deep inter-generational understanding as well. Like when I was the head of the adult literacy movement in South Africa it was always easy to get him to send messages of support and so on. But, because you can say, well, okay, the new government… There’s a term for it in South Africa now, like you know how they talk about the Millennials? There’s a term… ‘Born frees’! The born frees are those that were born after ’94. So now they’re ten years old. They got no… In fact, even if I take talking to the wonderful kids that are a part of my life, and who know the stories because they’ve heard it from me a thousand times, or they’ve been in the presence of friends, who when we get together we always tend to reminisce But still, often they think we’re exaggerating about how bad it was. They don’t really believe, because thankfully they are in more normal situations now, they attend schools with kids of different races, and its no big deal like it was for us. That was such a big thing. So the one thing about Mandela’s leadership is that he was not only a strong leader showing the importance of understanding the appropriate role of individual leadership. But he was always collective-minded, understanding that the wisdom comes from a range of people. For example, his relationship with the other senior leadership of the ANC was critically important to him, like Walter Sisulu was his confidant right until he passed away, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada.

AP: I wanted to ask you about Ahmed Kathrada.

KN: So Kathrada was the youngest of the Rivonia trialists…

AP: Of the what?

KN: The Rivonia trialists. Rivonia was a farm where they were captured from and the trial was known as the Rivonia trial.

AP: Mandela was part of that?

KN: Yes, that was the trial where he got life imprisonment.

AP: What were they trying to do?

KN: They had some explosives…Probably, in military terms, it was not even security training 101.

AN: Kindergarten.

KN: Actually, maybe I should take that back, because at that time maybe it was as sophisticated as you could get. But the other thing about Mandela which is really important was his passion for peace, because when he came out of prison he was unequivocal about the need to eliminate violence from the politics of South Africa. I remember this one speech, he went into Durban where there was a huge conflict between the ANC and Chief Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party, and it was Mandela’s force of character, his strength with humility, and so on. I mean quite often I think leaders are put into positions of unilateralism where they’re not prepared to deal honestly with their people about the ambiguity of leadership, because sometimes there are situations where you need a leader to be more assertive and maybe even less consultative, and in other situations, normally, I would say that’s a better style of leadership.

AP: Being consultative?

KN: Because then the responsibilities are shared more broadly and those who have responsibility for decisions have a greater investment in them… And as President, in the five years Mandela was there he was a very hands-off President, I would say, Thabo Mbeki did a lot of the day to day management of Cabinet Ministers and so on. And de Klerk was the other Deputy President, there were two Deputy Presidents in the first Cabinet. So I think that the kind of leadership that we need to revisit now as we reflect on one of the greatest leaders that walked this planet is, given where the world is, for example, should leaders take as given that the level of material privilege they assume, that comes with the role of leadership, should it be so vastly different from the day to day realities of often the majority of the people in their countries? So, for example, we have had some signs of positive actions such as the current President of Malawi, first woman to head up Malawi, and she, for example, sold off the Presidential jet. We just assume that the norm of leadership is living the life. So therefore you can see that there are times when leaders have to honestly say to their people, this is a time of austerity and we need to…

AP: Tighten our belts.

KN: …tighten our belts, people are thinking, well its easy for you to say. Its going to mean nothing to you because it will have no material effect on you, given that you have so much of excess income anyway, from what it takes to meet your basic needs. And so I think there needs to be a conversation. If there’s something that should come out of Mandela’s death right now, I would think there has to be a conversation about equality, and its importance, because every problem we have here is a world out of balance. I mean to have less than 200 of the wealthiest people in the U.S. be equivalent of, own more than, 65% of the American people, there’s something wrong with that system, where people have so much that they don’t need and they start being silly, and engage in exuberant consumption which is completely self-serving, and so on. And in that sense Mandela did not… and it was also the issue of his age and all when he came out, because, and don’t forget, he was cut off from the world for 27 years. Its amazing how he just appeared to fit smoothly into that world. But there’s a lot that he had missed in absolute terms. And so I don’t judge him too harshly on this, but the fact is, you know, he didn’t really fundamentally challenge the structural injustices in our economic life, and in that sense, I think that if you assume that he had spent, if you take the time that he was in prison, for example, and how much of that was lost. Because you know people don’t sufficiently acknowledge that he was not only about charisma and wisdom and all of that, he was also a person of intellect. He had a very very amazing intellectual gift, and I think his real gift was that ability to be able to walk one day with kings, queens and heads of state, and another day be as comfortable, and in fact, quite frankly, more comfortable, walking with regular people.

AP: That’s really good, you’ve given me a few private glimpses which aren’t out there which is great. I wanted to go back to the fact that you’re an Indian South African, and people don’t realize that many Indian South Africans participated in the ANC and in those struggles against apartheid. For instance I was quite surprised to see that this cellmate of Nelson Mandela was another Indian South African. What’s his name again?

KN: Ahmed Kathrada

AP: Right, so its not as exceptional as it seems?

KN: No, no, in fact, several South Africans of Indian origin were in Robben Island with Nelson Mandela. There was Mac Maharaj, Billy Nair, who spent twenty years there, and Zed, Uncle Zed we used to call him.

AP: Zed?

KN: Yes, Z-E-D, he spent fourteen years. Yeah, many, and disproportional to the size of the population in terms of this thing, but it was because of the legacy of Gandhi. During all of that there was quite a strong spirit of resistance in the community. Mandela was fond of Gandhi in terms of his life and work and writings, but the apartheid state, like all colonial regimes, maintained control by divide and rule, and in South Africa, the main form of divide and rule was on the basis of race, and not just that but also on the basis of language, so it wasn’t that it was just white, Indian, African, coloured, as they would’ve called it, but the African community was, the black African community were then broken up into Zulu, Xhosa, Tswana and the other African languages… your language and culture.

AP: Interesting, I have never heard that side.

KN: Yes, so there were people like myself who came through the liberation struggle, who were first influenced by Steve Biko, and were resisting the divisions of apartheid which were also historical and cultural divisions. Distinctions, let’s say, because obviously the people who came as indentured servants from India have a different history versus those who came to be defined as Coloured, whose numbers are in excess of three million; and their community was rich in culture…

AP: And the Coloureds are the hybrid people born out of contact between the Europeans and Africans?

KN: Yes, but the people who were so defined have forged themselves also into a rich community in their own standing. I think one of the richest cultures in South Africa in terms of music, dance, even rich art forms and so on, because there is also Malay influence, because there were slaves brought from Indonesia and Malaysia.

AP: Really, I didn’t know that.

KN: So, given all of these different influences, our response, those that came through the struggle like myself, when the state used to say white and non-white, we said we didn’t want to be non anything. So black then became the unifying identity. And Steve Biko’s big contribution was in the way that he defined black consciousness. He defined it as everybody who wasn’t benefiting from the privileges of white citizenship, and the ANC drew on and embraced that as well, and so for me my identity is very much first and foremost…

AP: A black identity, as a black person?

KN: Today, given the journey I’ve traveled, my first identity, it might sound silly but, is as a human being who is not bound by any man-made boundaries, but my second biggest identity is as an African whose identity is fundamentally linked to the African continent as a whole, and third it is South African, and then fourth, I would say, as a South African of Indian origin, and I don’t see any of those in contradiction. I think that they enrich each other in different ways.