In a bizarre twist on community policing lawmen in Jamaica have embraced iconoclasm–the erasure of painted memorials in this case–as a strategy. The photograph accompanying Honor Ford-Smith’s article in the Gleaner today (see above) pleading for the Police to be more sensitive to the social role images play in the communities that produce them is a case in point. What its caption doesn’t tell you is WHO Glenford ‘Early Bird’ Phipps was, or his relationship to Western Kingston and Matthews Lane in particular. It’s just another example of how Jamaican media occludes rather than reveals information.

“For some years now, the Jamaican police have been painting out murals in working-class communities in a symbolic battle with residents,” begins Honor’s article, a longer version of which she had sent me a week ago:

Judging by the public silence, many agree that destroying the murals will somehow help to obliterate donmanship. Perhaps this is understandable, given the fact that we’re all tired of living in fear and we’re tired of the global media marketing the idea that all Jamaicans are pathologically violent. It is hard then to ask what other meanings the police ‘clean-up operation’ might carry, or to suggest that we have much to learn from the murals themselves.

….

The destruction of the murals is an act of violent censorship of a popular street-art movement in Kingston in the guise of law enforcement. It is a violation of the right to freedom of expression that is guaranteed in the Jamaican Constitution. We may not like the murals. We don’t have to. That is not the point. Not liking them is not the same as denying the right of self-representation.

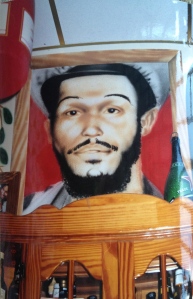

Just how much history is packed into murals and images produced by street artists can be seen by looking at the history of the very image the policeman is painting out in the Gleaner photograph above.

It happens to be a mural that I photographed a bit in 2004 during a close encounter with Zekes, the notorious Don of Matthews Lane, who brought Kingston to a standstill in 1997 when the police briefly arrested him. Glenford ‘Early Bird’ Phipps was Zekes’s beloved brother, brutally murdered in 1990 and memorialized by Zekes in an extensive series of murals on the walls outside and inside his bar (see below).

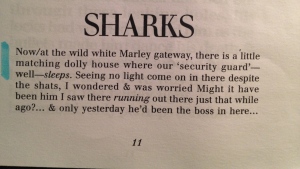

But even better than this, Early Bird was memorialized by none other than the famous poet Kamau Brathwaite in his long poem Trenchtown Rock. I’ve taken the liberty of photographing and reproducing below relevant portions from that poem so that you get a better sense of who Glenford Phipps was (“was a young Dreadlocks, [later I was to learn that he was known as “Early Bird”/catching his first too early worm of death that early All Souls Morning] his beautiful long hair like curled around his body making snakes like dance“), his sensational slaying outside the very building Brathwaite lived in, in which Phipps had also been resident, and his importance to the community he came from, to whom those murals would have been of great significance.

Many will say the murals are merely ‘a glorification of criminals’ and should be defaced for fear of their ‘grave effects’ on ‘poor Jamaicans’ etc. I quote from a Facebook response to my posting of Honor’s article. Frankly I’m always amazed at how many Jamaicans talk as if everything is black or white, easily distinguishable, devoid of ambiguity or nuance. Many of Jamaica’s national heroes were on the most wanted list of the colonial government in power at the time. How does a profoundly corrupt state determine criminality? If/When so many police personnel behave like criminals and in effect ARE criminals how do they determine whom to punish? And should the public support them in this? These are hypothetical questions but ones worth pondering. One of the interesting things brought out in Honor’s article on censorship is the fact that also memorialized in many of these communities are the fallen policemen belonging to them:

Some of the murals can be read as covert statements against police impunity and against police methods. But this doesn’t mean communities are against the police per se. If this were true, police from inner-city communities would not be memorialised. But they are. They, too, are mourned and remembered. Nevertheless, it is well known that Jamaica has a high rate of police violence that undermines public confidence in law enforcement.

Do we really have a right to erase the social history of communities in the name of hard policing? Really? What next?